Fabergé’s Animal Figures: When Realism Meets Fantasy

Among the many artistic marvels produced by the House of Fabergé, the hardstone animal figures stand apart for their extraordinary lifelike charm, craftsmanship, and psychological depth.

Neither simple miniatures nor mere ornamental objects, these sculptures encapsulate Fabergé’s rare talent for blending whimsy with exquisite realism.

Each creature—carved from Russia’s rich supply of semi-precious stones—captures not only the outward appearance of the animal but also its personality, mood, and even a hint of narrative. These miniature masterpieces were far more than decorative curiosities.

Commissioned by royalty, admired by collectors, and often exchanged as intimate gifts, they reflected the evolving tastes of a world fascinated by naturalism, Eastern aesthetics, and luxurious materiality.

At a time when most stone carvings were purely symbolic or religious, Fabergé’s creatures—rabbits, cats, owls, frogs, elephants—came alive with movement, character, and joy.

Animal Figures by Fabergé

Puffer, Kiwi (Collection Sir Charles Clore), Spherical field-mouse (Literature: Habsburg, 1897, p. 79) by Fabergé

Origins of Fabergé’s Passion for Hardstones

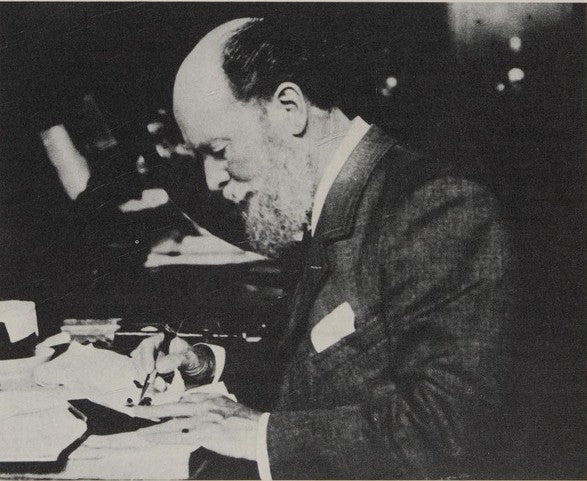

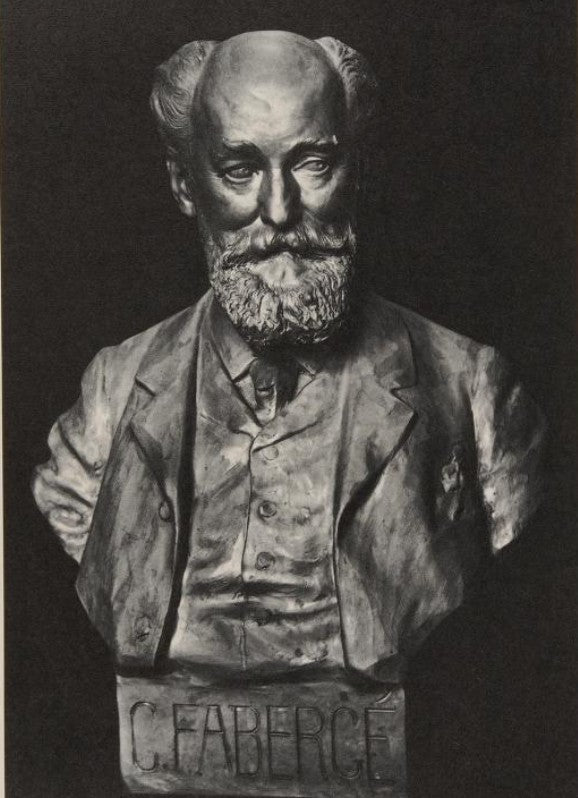

Peter Carl Fabergé’s journey into the world of hardstones was neither incidental nor driven by fashion—it was a deliberate artistic evolution shaped by his early exposure to Europe’s most prestigious stone-cutting centers.

His visits to Dresden, Idar-Oberstein, and Florence left a lasting impact, grounding his artistic vision in centuries-old traditions of hardstone craftsmanship.

In Dresden, Fabergé encountered the Saxon legacy of precious objects crafted from jasper, agate, and serpentine—stones mounted in gold and silver, often used for creating opulent boxes and ornamental vessels. Master artisans like Heinrich Taddel and Johann Christian Neuber, known for their intricate snuffboxes fashioned from Saxon gems, set the technical and aesthetic standards that would later influence Fabergé’s own creations.

His studies in Frankfurt brought him closer to Idar-Oberstein, a German town famous for its mastery in carving agates and chalcedonies. Fabergé’s connection with Idar-Oberstein wasn’t just inspirational—it became operational. Documents confirm that stonecutters from the region were later employed in Fabergé’s workshops in St. Petersburg.

Furthermore, his collaboration with the Stern workshop and carver Alfred Heine helped establish a pipeline for precision-cut stones, many of which found their final form in Fabergé’s iconic animal sculptures. Florence added a distinct artistic flavor to Fabergé’s repertoire.

Sniffing bloodhound carved by Alfred Heine, Bulldog - Museum Unter der Felsenkirche, Idar-Ober-stelin

The Opificio delle Pietre Dure, founded by the Medici, had produced religious figures and mosaic tabletops in polychrome hardstones for centuries. Fabergé absorbed this decorative opulence, and it’s likely that his signature use of purpurine—an intense red glassy material once thought to be uniquely his—was in fact inspired by similar 17th-century Florentine techniques.

This triad of European centers provided Fabergé not only with stylistic foundations but also access to a rich palette of technical methods and raw materials.

Animal Figures by Fabergé

Russia’s Native Stone-Cutting Traditions and Fabergé’s Workshop Beginnings

While Fabergé drew inspiration from the great stone-cutting centers of Europe, he also inherited a rich local tradition of hardstone carving. Russia had long cultivated its own expertise in lapidary art, with centers such as Ekaterinburg, Peterhof, and Kolyvan producing imperial objects since the 18th century.

These workshops supplied the Romanov court with decorative stone vases, monumental urns, and mosaic tabletops made from native materials like malachite, jasper, and polychrome marbles. However, the limited technology available in these Russian centers meant that the harder stones—such as agate, obsidian, quartz, and rock crystal—often had to be cut abroad.

Upon returning to Russia in 1870, Carl Fabergé sought to expand his father’s modest jewelry workshop by introducing hardstone objects into their repertoire. His appointment of Erik Kollin as first head workmaster reflected this ambition. Kollin’s early work included archaeological-style mounts and hardstone objects crafted from smoky quartz, often set in yellow gold reminiscent of 16th-century design.

Fabergé’s goal was not to rely on precious gems and metals for value, but rather to highlight the sculptural and chromatic qualities of the stones themselves, elevating their artistic presence through refinement and imaginative form.

Barking dog, Mouse, Cat and Toad by Fabergé - The Brooklyn Museum (Bequest Helen B. Banders)

Fabergé obsidian seal lying on a rock-crystal ice floe

Fabergé’s Favorite Stones and Their Unique Qualities

Rather than focusing on diamonds or sapphires, Fabergé turned to Russia’s own vast geological wealth to find expressive potential in nephrite, bowenite, jasper, chalcedony, and other semi-precious stones. These materials were not chosen arbitrarily; each was selected for its unique hue, texture, or ability to suggest the color and form of natural subjects.

Among his favorites was nephrite, a spinach-green variety of jade flecked with dark inclusions—ideal for frogs, snails, and leaf-like textures. Bowenite, a creamy green serpentine, was commonly used for handles, desk sets, and small animals like elephants.

Jasper, particularly a gray variety found near Kalgan, was used for sturdy, naturalistic bodies, while lapis lazuli—with its deep ultramarine tone and flecks of golden pyrite—offered a celestial brilliance suited for decorative bases or exotic birds.

Other materials, such as rhodonite (a pink stone with black veins) and purpurine (a deep red, glassy material developed in 19th-century Russia), were prized for their vibrant color effects. These stones weren’t merely decorative—they enabled Fabergé to convey personality, movement, and symbolism in his carvings.

Goose, Fledgling crow (Provenance: Miss Yznaga della Valle), Stylized crouching toad, Duckling by Fabergé

Seated mandrill by Fabergé (Snowman, 1962/64, ill. 253 - Catalog of the Armory, 1964, p. 166/7 - Rodimtseva, 1971, p. 20, ill. 10 - Armory Museum, Kremlin, Moscow)

Seated mandrill by Fabergé (Snowman, 1962/64, ill. 253 - Catalog of the Armory, 1964, p. 166/7 - Rodimtseva, 1971, p. 20, ill. 10 - Armory Museum, Kremlin, Moscow)

"Kara Shishi" - Mythical animal, probably inspired by a Chinese original - by Fabergé (State Hermitage, Leningrad)

From Rough Stone to Fine Object: The Workshop Process

Fabergé’s animal figures were not simply the result of technical skill; they represented a harmonious collaboration between stone carvers, goldsmiths, enamelers, and modelers.

Much of the stonework was carried out at Karl Woerffel’s factory on the Obvodny Canal, which Fabergé eventually purchased and entrusted to Alexander Meier. Two of the most gifted craftsmen working there—Derbyshev and Kremlev—were responsible for producing many of the refined hardstone pieces, and their work was so skilled that it was later sought out even by competitors such as Cartier.

The production process was meticulous. Each animal began with an observational sketch or wax model, sometimes based on live studies—as was the case with the famed zoo project for Queen Alexandra.

Stone segments were carved individually, then joined with such finesse that seams became invisible to the naked eye. Once the animal was assembled, additional details such as gold beaks, ivory tusks, or gemstone eyes were added under the direction of Fabergé’s chief jeweler.

The final touch often came in the form of colored enamel, which harmonized the object’s palette and accentuated its narrative quality.

Animal Figures by Fabergé

Kangaroo, Piglet, Seal, Caricature of a rhinoceros (Provenance: Esward James / Mrs. Josiane Woolf) by Fabergé

Eastern Inspiration: Netsuke and the Art of Capturing Essence

A surprising yet profound influence on Fabergé’s animal figures came from the Japanese tradition of netsuke—small, intricately carved toggles used to secure pouches on kimono sashes.

Fabergé himself owned a personal collection of over 500 netsuke, many likely acquired from the shop "Japan" on Nevsky Prospekt in St. Petersburg. These miniature carvings fascinated him not just for their craftsmanship but for their ability to express the very spirit of animals through compact, tactile forms.

Like the Japanese artisans, Fabergé and his team strove to capture the personality and movement of animals, not merely their physical likeness. The curve of a neck, the twist of a tail, or the glint in an eye—these subtle cues brought emotion and vitality to his creations.

Some animals were intentionally whimsical or exaggerated in proportion, echoing the humorous charm of netsuke. Others—like a rabbit caught mid-leap or a puppy stretching in play—evoked moments of natural spontaneity, frozen forever in stone.

This shared appreciation for "tactile values" was more than aesthetic. It invited interaction. Whether carved in polished bowenite or velvety obsidian, Fabergé’s figures were designed to be held and admired from every angle, much like their Japanese counterparts.

The influence of netsuke was not mere imitation, but a dialogue between cultures—where Fabergé translated Eastern philosophies of form and essence into a distinctly Russian idiom.

Table-clock shaped like an Indian elephant by Faberge / Provenance: According to tradition, this piece originates from the collection of Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna of Russia, born Princess Dagmar of Denmark. The choice of red and white—the royal Danish colors—may symbolically reference her heritage. The clock was acquired in Russia in 1925 by the father of the present owner, renowned collector Sam Josefowitz.

Cockerel, Elephant with Two Raised Legs, Climbing Frog, Royal Danish Elephant by Fabergé – The Wernher Collection, Luton Hoo

Mystic Ape, Mouse, Rabbit by Fabergé – Literature: Snowman, 1979, p. 65; Munn, 1987, p. 39 / Mrs. Josiane Woolf

Fabergé’s Color Language in Animal Carvings

One of Fabergé’s most compelling artistic strategies was his imaginative use of color—not merely realistic, but evocative, and sometimes delightfully surreal.

Unlike ivory or wood, hardstones offered a kaleidoscope of natural hues, and Fabergé used them to enhance both species and emotion. His choices were deliberate and narrative-driven.

For instance, he carved a toad from speckled amazonite, a pig from pink aventurine, and an earthworm from pink agate with dark inclusions. The feathers of a young Ural owl were rendered in black-and-white granite, while a tiger might be composed of striped agate in orange and black bands.

Fabergé owl made of gray-white granite (formerly Nobel Collection)

In more elaborate compositions, Fabergé combined stones to enhance realism: a toucan crafted in gray jasper featured a contrasting orange agate beak; a cockerel carved from obsidian sported a vibrant purpurine comb.

Sometimes, however, Fabergé embraced whimsical or surrealistic coloration to heighten charm. He made red elephants, green baboons, and blue rabbits—an artistic precursor to the playful imagination of 20th-century animation.

These choices were not mistakes, but acts of creative license, transforming decorative sculpture into objects of fantasy and delight.

Seated chinchilla, Sturgeon, Angry Baboon (Bainbridge, 1949/69, pl 85), Flamingo (Snowman, 1979, p.43), Dachshound by Fabergé

Animal Figures by Fabergé

From Zoological Study to Royal Collection: The Sandringham Commission

The most celebrated and extensive collection of Fabergé’s animal figures was born from Queen Alexandra’s love of animals.

As the sister of the Russian Dowager Empress, Alexandra admired Fabergé’s work and often received his pieces as gifts. But in 1907, a special idea emerged: to immortalize her beloved animals from the Sandringham menagerie as birthday gifts.

Under the coordination of Fabergé’s London agent, Frank Bainbridge, and with King Edward VII’s blessing, modelers Boris Froedman-Cluzel and Frank Lutiger were dispatched to Sandringham to sketch the Queen’s favorite pets from life.

These wax models were then sent to St. Petersburg, where they were transformed into highly detailed hardstone carvings using bowenite, agate, nephrite, and obsidian—each chosen to reflect the animal’s actual coloring and character.

The first set of figures was presented to the Queen in 1908. Over time, the collection grew to include over 350 different animals, each unique in material and execution. Edward VII himself contributed additional commissions, always insisting: "We do not want any duplicates."

Attribution Challenges and the Rise of Competition

While Fabergé's animal figures remain masterpieces of craftsmanship, their authenticity presents challenges even to seasoned collectors. Unlike his more famous Imperial Easter eggs, most animal carvings were unsigned, bearing no hallmark or engraved signature.

A few pieces were discreetly marked with "FABERGÉ" or the initial "K", and even fewer bore the assay marks of Henrik Wigström, Fabergé’s head workmaster. Occasionally, Perchin marks appeared, but they were rare exceptions. This lack of consistent signature creates a grey zone of attribution, especially as several rival workshops began producing similar hardstone animals.

Cartier, for instance, was a formidable competitor, actively seeking to poach Fabergé’s clientele. Documents from the Cartier Archives reveal that by 1904, Cartier had begun ordering hardstone carvings from Russian lapidary Svietchnikov and even considered setting up their own cutting operations in St. Petersburg.

Other competitors such as Ovchinnikov, Sumin, Dennisov-Uralski, and Britzin also established workshops, sometimes copying Fabergé’s style so precisely that today it is nearly impossible to distinguish certain pieces without provenance or expert analysis.

Because hardstone animal figures lack the supporting evidence often used to verify other objets de vertu—such as enamel quality, metalwork, or maker’s boxes—the burden of attribution falls heavily on craftsmanship alone.

The elegance of line, anatomical realism, and subtle humor must be assessed with a critical yet intuitive eye, making evaluation a subjective and specialized art.

Playful cat (Provenance: Edward James), Seated spaniel (Provenance: Baron von Blucher, Geneva), Capercailzie cock and Squirrel (Provenance: Miss Yznaga della Valle) by Fabergé / Mrs. Josiane Woolf

"Field Marshall", the shire horse by Fabergé / The British Royal Collection

A Legacy of Inspiration and Innovation

Fabergé’s hardstone animal figures established a new benchmark in artistic lapidary work—blending nature, humor, and technical sophistication in ways that few others dared.

His designs pushed the limits of what could be achieved with materials like agate, nephrite, bowenite, and purpurine, setting standards of excellence still admired by jewelers and collectors today.

Modern artisans continue to draw from Fabergé’s aesthetic and technical innovations, whether in the use of colored stones for expressive effect or in sculpting with precision that respects both material and subject.

The psychological nuance in his animal figures—such as a timid rabbit or a mischievous kitten—has influenced not only jewelry design but also sculpture and decorative arts more broadly.

More than a century later, Fabergé’s animal carvings remain beloved by collectors and curators worldwide. Museums like the Hermitage, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Buckingham Palace safeguard his creations not just for their material beauty, but for their cultural and artistic resonance. They stand as enduring reminders that true mastery lies in bringing inanimate materials to life—with sensitivity, humor, and brilliance.

Today, this collection remains one of the most treasured legacies of Fabergé’s animal sculpture, blending affection, observation, and technical brilliance in a deeply personal royal narrative.

"Caesar", King Edward VII's Nortfolk terrier, Amorous macaques, Spherical Indian elephant by Fabergé / The British Royal Collection

Japanese tiger by Fabergé

Royal Danish Elephant by Fabergé

Did You Know? Fascinating Facts About Fabergé’s Animal Figures

- Royal Zoo in Stone: Queen Alexandra loved animals so much that her friends commissioned Fabergé to replicate her favorite pets from Sandringham Zoo in hardstone miniatures. Over 350 unique animal figures were eventually created for the British royal family—no duplicates allowed!

-

Inspired by Netsuke: Fabergé owned a collection of over 500 Japanese netsuke—small carved toggles that inspired his compact, humorous animal figures. Like the netsuke artists, Fabergé captured emotions with subtle curves, expressions, and gestures.

- Secret Signatures: Most of Fabergé’s animals were not signed, making authentication difficult. When they were, discreet carvings like “FABERGÉ” or initials appeared under a foot. Very few carry full hallmarks, adding to their mystery.

- Tactile Art: Fabergé’s animals weren’t just visual wonders—they were meant to be held and touched. He emphasized “tactile values,” carving fur, feathers, and skin textures with uncanny realism.

- Colorful Whimsy: Some animals had a surreal twist—red elephants, blue rabbits, and green baboons—showing Fabergé’s playful imagination long before Walt Disney’s world of color!

- Collector’s Challenge: Because animals were rarely signed or hallmarked, their attribution relies almost entirely on craftsmanship quality. That makes each genuine piece not only precious—but also a bit of a detective story.

Bibliography & Photo Credit: Fabergé by Geza von Habsburg - Geneva, Feldman Editions, 1988.