From Pharaohs to Priests: Inside Egypt’s Royal Jewelry Workshops

The jewelry of ancient Egypt is steeped in mystery and mysticism and has served as a lasting source of inspiration for modern design.

Yet one of the lesser-known aspects of this legacy lies in the story of the artisans who crafted these treasures. Where did they draw their inspiration? What materials did they use to meet the expectations of pharaohs and nobles?

Across cultures and time, jewelry has always symbolized wealth and power. In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was showered with magnificent gifts from birth to death—each piece not merely decorative, but imbued with ritual and political significance.

The history of ancient Egypt is rich and vibrant. One of the culture’s most striking traits was the people’s deep appreciation for ornamentation. Whether young or old, rich or poor, Egyptians adorned themselves with jewelry. From everyday wear to ceremonial regalia, adornment was a vital part of identity.

As evidenced by the vast variety of jewelry uncovered across Egypt, the ancient Egyptians embraced grandeur and expressed a remarkable cultural sophistication. Their decorative arts have garnered global admiration and scholarly study.

Tutankhamun's golden funerary mask at the Egyptian museum in Cairo (Source: Roland Unger via Wikimedia Commons)

Egypt accumulated a vast treasure trove of gems and opulent adornments over the centuries—a legacy of artistic brilliance and spiritual devotion.

This love for self-adornment reflected not only a refined sense of beauty but also deep symbolic meaning. Anklets, bracelets, crowns, earrings, necklaces, brooches, girdles, and protective amulets were all part of their aesthetic and spiritual expression. Gold offerings were also made to gods and spirits as sacred tributes.

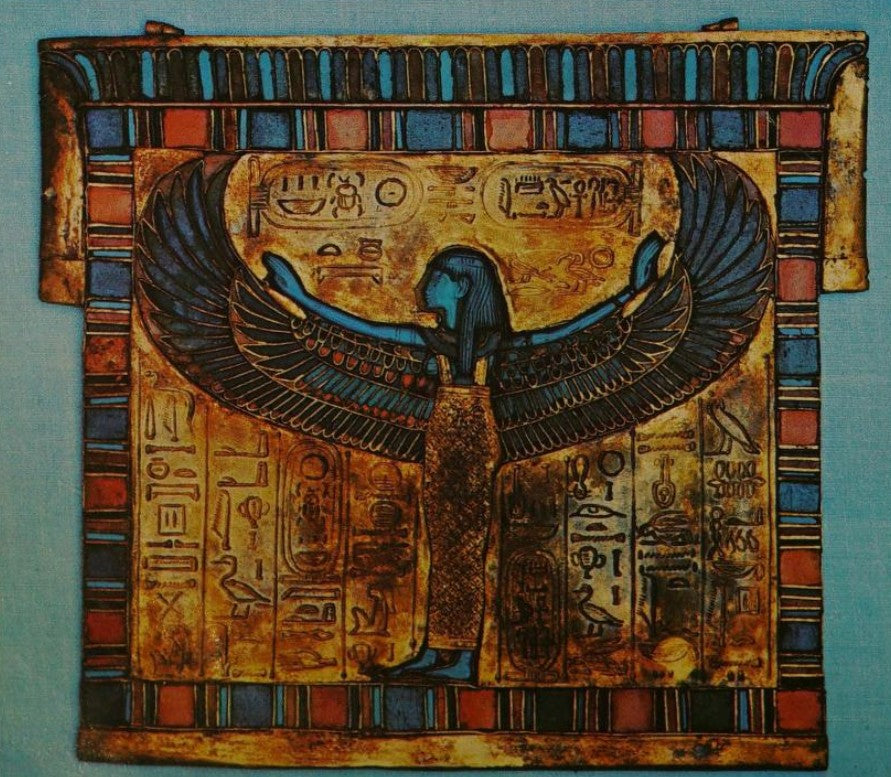

Vulture pectoral of Tutankhamun representing Nekhebet via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Rebus pectoral of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Massive scarb bracelet of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

The Craftsmen of Egypt

Gold was regarded by the Egyptians as the most precious material for jewelry-making. The tombs of the pharaohs reveal the remarkable skill and artistry of ancient goldsmiths.

Interestingly, in the document known as The Satire on the Trades, the esteemed position of the scribe is humorously contrasted with the hardships of manual labor. While this satire diminishes the value of other professions, historical evidence suggests that artisans who crafted fine jewelry for the elite held considerable status—though this is sometimes obscured by literary caricature. As Cyril Aldred explains in his book "Jewels of the Pharaohs : Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period", the artisans were both respected and influential.

the Aldred notes that Apuia, one of Amenophis’s most prominent goldsmiths, had sufficient influence to commission a stately tomb for himself in the necropolis of Memphis. His son, Pa-ren-nefer, who served under Pharaoh Akhenaten, was honored with a large sculptured tomb in Thebes and another significant one at Amarna.

Pa-ren-nefer was close enough to the king to be named his personal cupbearer—an intimate and trusted role. While senior artists and supervisors enjoyed prestige and wealth, it is likely that apprentices and journeymen who labored over charcoal braziers, wielding blowpipes and tongs, occupied a lower social tier.

The mortuary artisans of Deir el-Medina, who were favored by the state, provide further evidence that highly skilled craftsmen in elite trades commanded both social respect and financial stability.

Although no formal guilds of goldsmiths are documented, it is likely that the jewelry trade was concentrated among a few prominent families working in key locations, where expertise was passed down through generations.

Memphis, the ancient capital in the north, is believed to have been the most important goldsmithing hub. The city was under the patronage of the artisan god Ptah—a tradition that endured into the Middle Ages and was later echoed by the metalworkers of Cairo’s bazaars, as Aldred recounts.

Amulets and Bracelets of Tutankhamun (Source: Claude Valette via Wikimedia Commons)

It is also possible that skilled laborers from other regions of the Mediterranean were drawn to Egypt’s flourishing artistic centers, enticed by both cultural prestige and patronage opportunities during periods of prosperity.

Because gold was a state-controlled resource, and rulers had a vested interest in its symbolic power, goldsmiths typically worked in royal workshops or within temple cults under the monarchy’s protection.

Yet when war, political chaos, or economic decline disrupted patronage, these artisans—valued for their rare skills—could relocate wherever their craft was welcomed. Their tools, techniques, and artistic legacy ensured that Egyptian goldsmiths remained respected figures in the cultural tapestry of the ancient world.

Two scarab bracelets of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Detail of the diadem of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Winged scarab pectoral of Tutankhamun, with Isis and Nephthys via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Gold rigid bracelets of queens of Tuthmosis III via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

The New Kingdom

By the time of the New Kingdom, the methods used by Egyptian goldsmiths had become so widespread across the Near East that it is sometimes difficult to identify certain pieces of Egyptian goldwork as uniquely indigenous in either design or technique.

Beyond royal commissions, goldsmiths also worked for elite patrons, including the gods worshipped in major urban centers—most notably Amun of Thebes. Although the exact locations of five goldsmith overseers’ tombs have been lost, three of them were wealthy enough to be buried in the prestigious Theban necropolis. Two other goldsmiths, possibly tied to the royal court, are also known to have had tombs in Thebes.

Today, museums across the globe house numerous high-value artifacts created for or by these skilled artisans. While these men were undoubtedly talented, many did not execute the jewels themselves—especially when the designs were part of a long-standing tradition passed down with minimal innovation. However, the court jewels of each new reign often required revisions, whether subtle or bold, to align with shifting royal tastes.

Some pieces may have introduced inventive flourishes to time-honored motifs, as seen in the jeweled pectorals from Dahshur and Lahun. Each one is distinct. As Aldred notes in "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period", most were crafted by uninspired hands—except for one, attributed to Princess Sit-Hathor-Yunet, which appears to be a faithful reproduction of an earlier masterpiece.

Although primarily decorative artists, the finest jewelers of the New Kingdom were likely literate and classically educated, with knowledge extending beyond metalwork to drawing and design. These men were not only craftspeople but also thinkers, designers capable of conceptualizing objects across various applied arts.

Neb-Amun, chief sculptor under Amenophis III, exemplifies this. Tomb paintings show him overseeing projects involving not only sculpture but also metalwork, carpentry, and more. His involvement highlights the interdisciplinary approach of Egyptian master artisans.

Interestingly, during the New Kingdom, the Second Prophets of Amun at Thebes played an administrative role in overseeing commissions for both the king and the god Amun. Tomb illustrations depict these officials inspecting temple workshops, including those of the goldsmiths. One particularly detailed scene shows an officer observing the weighing and distribution of gold and silver, which would then be allocated to various projects.

An example of the scale and prestige of such works can be found in the burial gifts commissioned by Amenophis III for his in-laws—lavish objects adorned with gold, silver, semi-precious stones, and colored glass, all crafted under the direction of their son.

The title "Greatest of Craftsmen", used for the high priests of Ptah—the artisan god of Memphis—suggests they held authority over a wide array of artistic production in earlier dynasties. Reliefs from the Old Kingdom often show dwarves managing the presentation of completed ornaments, reflecting both symbolic and functional roles in the workshops.

As in modern times, goldsmiths and silversmiths were the premier jewelers. Yet, as noted in the Hood Papyrus, they were just one group among many specialized artisans. According to Jewels of the Pharaohs, this diverse and structured workforce shaped one of the most refined jewelry traditions in the ancient world.

Earrings and necklaces of Queen Twosre via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Jewelry of Queen Mereret via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Armlet of Queen Ah-hotpe in the form of a vulture via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

The Structure of Ancient Egyptian Jewelry Workshops

In the hierarchy of ancient Egyptian artisans, the neshdy—the craftsman of precious stones—ranked just below the nuby, or goldsmith. Unlike the goldsmith, whose work was primarily in metal, the neshdy specialized in lapidary arts, shaping and polishing gemstones that would embellish not only jewelry but also ceremonial furniture and sacred objects.

Working alongside them was the baba, the faience-maker, who mastered the art of firing quartz paste into vividly colored, glassy objects—typically in turquoise blue or emerald green, but later evolving into multi-colored or marbled effects. In the New Kingdom, these artisans likely extended their knowledge into the production of actual glass, bridging the gap between traditional faience and emerging material technologies.

Another key figure in the jewelry-making fraternity was the setro, a skilled assembler of broad collars—the elaborate multi-row necklaces iconic to Egyptian fashion. These pieces were composed of countless tiny components and required both technical ability and a refined eye for color and proportion. The setro worked with materials provided by the fru weshbet, or bead-makers, who were possibly a subtype of baba if they dealt with faience and glass, or perhaps operated under the neshdy if they worked in semiprecious stone.

The sheer volume of beads found in Egyptian tombs—crafted in diverse materials and techniques—attests to the labor-intensive nature of this sector. Reliefs and murals often depict jewelers working alongside metalsmiths and joiners, suggesting shared workshops or close collaboration under centralized oversight. This integration was likely enforced due to the precious metals involved: gold and silver had to be carefully weighed, logged, and distributed under watchful supervision.

Sithathoriunet's pectoral bearing Senusret II's praenomen (Source: John Campana via Wikimedia Commons)

Crown of Princess Khnumet via "Jewels of the Pharaohs : Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Gold for the King, and for the People

Officially, gold and silver were reserved for the king and the gods—particularly for Amun, whose temples were endowed with vast gold-bearing lands in Nubia and the Eastern Desert. Nonetheless, archaeological evidence suggests that significant quantities of precious metal found their way into private hands. Even modest, untouched tombs sometimes yield gold amulets, beads, or simple jewelry pieces, indicating that common citizens could legally own and be buried with such treasures.

Royal gifts, honorary decorations, and ritual weapons were also crafted in gold, while bullion was used to reward loyal servants. The fact that tomb robbery was severely punished and often detected suggests a system in which private ownership of gold was both monitored and permitted to a degree—implying that many jewelers likely took on private commissions at home, in addition to their work in temple and palace ateliers.

According to Cyril Aldred in Jewels of the Pharaohs, the tools used by these jewelers were strikingly primitive. Their furnace consisted of a simple ceramic pedestal bowl filled with glowing charcoal. The primary instrument was a reed blowpipe tipped with a narrow nozzle. Despite the limitations of such archaic equipment, skilled craftsmen were able to solder, melt, and even fuse metals with precision—depending on their deep understanding of how to control heat and select the proper solder for each task.

It is nothing short of remarkable that, with such rudimentary technology, Egyptian goldsmiths produced some of the most enduring and exquisite jewelry in human history. Each piece stands as a testament not only to technical ingenuity but also to a culture that revered beauty as both divine and deeply human.

Pectorals of Amenophthis via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Basic Instruments of the Ancient Jeweler

By the time of the New Kingdom, Egyptian metalworkers had significantly improved their methods. The traditional method—where several men would direct air into the fire using multiple blowpipes—was gradually replaced by the introduction of a foot-operated blast furnace. This new system, powered by leather bellows controlled by cords and foot pressure, resembled the technology used by African blacksmiths in more recent centuries.

Large clay crucibles were used to melt down gold dust, scrap, or ingots, whether to cast pieces into molds or to reforge them into larger masses suitable for hammering into sheets. These crucibles were suspended just above the heat by two flexible rods—likely green branches—secured at both ends.

Tools remained surprisingly basic. Polished pebbles were used as hammers to shape gold and silver. Though seemingly primitive, these stones were highly effective: their flat sides worked well for planishing, while the domed surfaces functioned much like modern raising hammers. The blocks upon which metal was hammered were likely made of wood, possibly wrapped in hide to reduce the shock of striking a hard, unyielding surface with a hand-held stone.

Egyptian wall reliefs show artisans using only these basic tools, but archaeological finds suggest some advances. Two similarly shaped hammerheads—one limestone and one bronze—now housed in New York collections, resemble modern blacksmith hammers, complete with a flat end and a wedge-shaped cutting edge. The limestone hammer was likely used for more delicate metals like gold.

To grind and polish, artisans used sandstone and quartzite abrasives of varying fineness. These stones were often used in combination with fine quartz sand, sieved through progressively finer cloth to achieve a smooth finish on stones and metal surfaces.

Without modern shears, ancient smiths had to rely on chisels made of copper or bronze to pierce and cut metal. For drilling holes, they used awls or bow drills depending on the material, while tongs—likely also made of copper or bronze—were employed to manipulate hot metal over the charcoal brazier.

Scarab and falcon pendents of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"

Legacy of the Ancient Egyptian Jeweler

Despite their seemingly crude tools, ancient Egyptian jewelers produced pieces of astonishing complexity and beauty. The gems found at Dahshur and Lahun bear witness to an unmatched mastery of craft achieved through practice, intuition, and ritual knowledge.

Jewelry in ancient Egypt was never just decorative—it was imbued with meaning. Faith, mysticism, and symbolism shaped every creation. Pieces were chosen not only for aesthetics but also for their spiritual significance, often serving as protective talismans or symbols of divine favor.

Blessed with access to abundant gold, silver, and precious stones, Egypt's artisans created an unparalleled legacy of adornment. Their work included not only necklaces, armlets, rings, and earrings but also intricate pectorals and brooches designed to honor gods, kings, and the afterlife itself.

These treasures—recovered from tombs, temples, and ancient ruins—stand today as testaments to the genius of Egyptian goldsmiths. Ancient chroniclers and modern historians alike marvel at the abundance and refinement of this heritage, confirming Egypt’s place as one of the greatest cradles of jewelry artistry in human history.

Cover photo: Nut pectoral of Tutankhamun via "Jewels of the Pharaohs: Egyptian jewelry of the Dynastic Period"